Susan M. Wadsworth, Rindge NH and Shushan, NY

I’m not exactly sure when I became interested in things Japanese. I grew up in Squirrel Hill in Pittsburgh, next to an old, decaying estate of six acres surrounded by once-beautiful gardens. There was one cool, dark “Asian” garden that led to an old Japanese tea pavilion, which was what I remember it being called. Of course, I am more apt to imagine nineteenth century ladies having English tea in that pavilion, brought down there by servants, with a silver teapot, porcelain cups, scones and little sandwiches. I don’t see it being used for the traditional Japanese tea ceremony at all. But it was probably built during a wave of Japonism that spread throughout the U.S. in the late nineteenth century. When I was growing up in the sixties, this little tea house became decrepit and was vandalized more than once. But I wonder if this isn’t where the seed of my love of Japanese culture was planted.

My paternal grandmother also visited Japan early in the twentieth century, but she died long before I was born, and all I have are old glass slides of that trip. At one time, I was hoping that she might have visited where I did over one hundred years later, but the slides were so fragile I put them away rather than break more than one.

As an art major, I learned, of course, about the Japanese influence upon the Impressionists and early Modernism. But it wasn’t until I started training in the martial arts (Kosho Shorei Ryu as well as Japanese sword) that I began to learn Shodo, or the art of the brush. What we learned was a bare introduction, and I craved more. So I bought books and practiced the lettering on my own. I also studied almost a full year of Japanese with Ritsuko Sullivan Sensei at Fitchburg State, but (as a busy professor myself), I was not the best student and failed to learn as much as I should have.

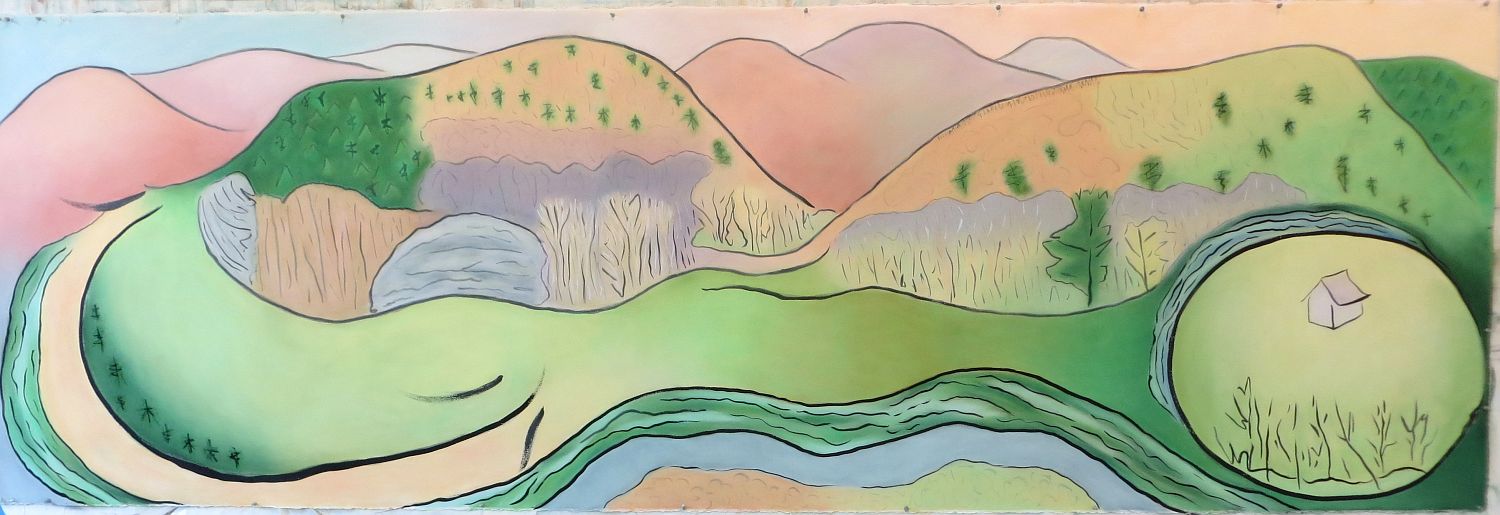

As an abstract artist in the tradition of the American Modernists and Canadian Group of Seven, I am always looking at the landscape. Near my home in rural NH, white pines soar high above the other trees around our pond. Soon I realized that these tree silhouettes looked a bit like Asian characters, or kanji.

I tend to use the Japanese word kanji for the Asian characters in my work. I also use the term “calligraphy,” although I am more apt to understand, and use, the more familiar block form of these letters, which still seem “calligraphic” compared to Western lettering.

In ancient Chinese art, these characters are called hanzi, whereas kanji is a Japanese term. In ancient Chinese scrolls, often poems were added to the side of the images, or the pictures would alternate with a poem or explanation. Thus words were added directly to the artwork. There would also be abundant red stamps, signifying who had once owned the works. Few westerners have added such words to their works, and I don’t know of any western works with the collectors’ names scribbled across the works. Imagine how that would devalue a van Gogh!! (Van Gogh, however, did include some kanji himself in the side margins of Flowering Plum Orchard. When I asked Sullivan Sensei about this, she said that the words seemed to be from an address or something like that. Thus they did not necessarily make sense with the plum blossoms nor within themselves. But it was still an effort that shows how much van Gogh appreciated all things Japanese.)

In my work, I want to have the kanji make more sense. I’ve had a lot of fun with that, adding certain characters to the forms themselves or to the background. Generally the kanji I choose mean things like Eternity, Water, Mountain, Life, Peace, Serenity, Yin or Yang, Woman, etc. I have now begun writing their meanings within my titles, since I cannot always remember all the kanji from works that I finished some time ago.

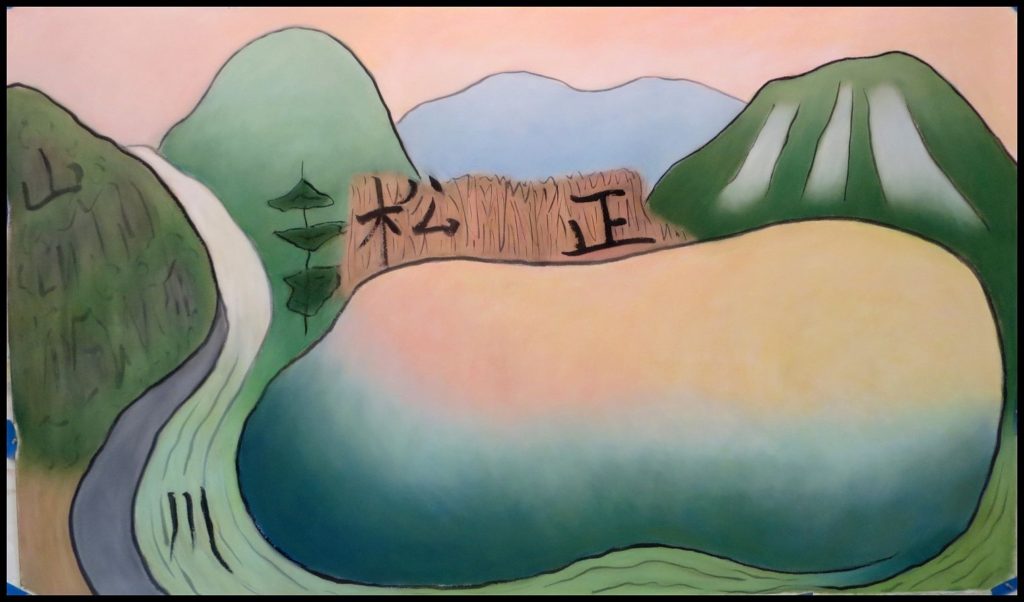

Now I am experimenting on integrating the kanji into and around tree branches, as in a very new piece entitled Route 100. Here the kanji signify yama (mountain), river, pine tree, and correct or true.

I don’t include kanji in all my works of art, only where they seem to be called for. Not even all the works set in Japan have kanji or even ink outlines. But by using these characters, it seems to be a way to integrate some of the aesthetic ideas of the East and the West. My flattened, abstracted forms already echo Chinese and Japanese works. The use of ink outlines makes a stronger form than the pencil from my previous works, but, then again, I do not use ink in all my works. Using ink and kanji is one way to incorporate Easterm culture and even Asian philosophy directly into what would otherwise be mostly Western landscapes.

I wonder, of course, if anyone recognizes these hanzi or kanji, and if anyone can see their connection with the artwork. Often they are chosen as much for their shape (as resembling tree branches or other forms) as much as for their translated meaning. If anyone has comments about this, please make a comment here or contact me at susan.wadsworth@gmail.com.